Letter to the Moment I Wish I Could Take Back

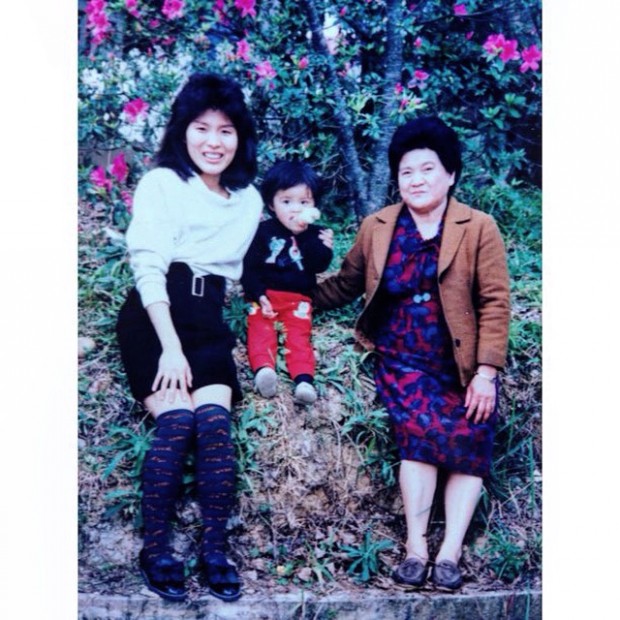

Above: 1987. My mum, me, and my grandma, looking totes hip.

From Women of Letters, June 2015. Curated by Marieke Hardy and Michaela McGuire.

I was 28 going on 29 the first time I saw a dead human being. Yes, I know, that is probably a reflection of my very sheltered, very lets-pretend-we’re-Caucasian middle class upbringing, but the fact of the matter is, death is not something we spoke about in my family.

I remember when I was 12, and my Grandad was sick – all my parents would say is “oh he’s got the badness, he’s got the bad in him” like a lyric from a Pitbull song. It wasn’t until 2 months later I found out he had actually died. In my family, the word “death” is never mentioned when you’re talking about death.

And so, when my mum asked me to go with her to Taiwan to see my grandma because she had some “rotten stuff” growing inside her, I kind of suspected what was coming.

I hadn’t been back to Taiwan for 10 years, and in the 20 years I’ve been in Australia I’ve only gone back twice – a fact the Taiwanese customs officer noticed immediately. He could barely contain his snide judgement as he flipped through my stiff, unused Taiwanese passport. “Your accent is very thick,” he sneered, somewhat unhelpfully of my mandarin. I glared at him and struggled past with my oversized luggage full of useless stuffed koalas, ugg boots, and macadamia nuts for all my relatives. “Welcome home.” He calls out from behind me as the door opens to reveal my foreign homeland.

Looking out the window of my uncle’s sedan at the passing city, I had faded, nostalgic, instagram-filtered visions of faces and places from my childhood. But I immediately questioned if it was real or made up. That’s the problem with being a storyteller. Memories aren’t just memories, they are stories that you are expected to mine for emotional truth. But how truly authentic can those memories be if I can see myself in them, complete with wide shots, close ups, and the occasional musical montage?

I noticed my uncle gawking at me from the rear-view mirror. “Is she married yet? Are there many Taiwanese men in Australia?” He asked my mum in the front seat, as if I wasn’t there. “Her? No. Corrie’s…ah, she has quite picky tastes. Also she’s very focused on her career.” My mum said, somewhat apprehensively.

I sat silently in the backseat and mulled over my mums words. “Picky tastes”. I mean, I guess she’s not lying, I guess you could call dating only Caucasian women “picky tastes.”

When I got to my grandma, I was stunned to see her so small, so frail. She was completely unconscious and would have these fits of pain that would make her entire body shake. The doctor insisted that she could still hear us fine, and that we should take turns to reassure her and to say our goodbyes. But I was dubious – frankly this sounded like bullshit doctors say to make you feel better.

My uncle and mum were the only siblings there, out of seven, and I could tell my mum was furious about it. But it was the first day of Chinese New Year. This was a time for family, feast, and celebration. It is terrible luck to start the new year off with a death, and we were all painfully aware that outside the hospital window, parades and fireworks were going off every other minute, punctuating the grim silence.

Slowly, the siblings trailed in one by one. My oldest aunt arrived, sobbing, her heart on her sleeve as usual. But she was immediately scolded by all the other siblings. Don’t you dare cry out loud, they said. It makes it more painful for the spirit to pass into the next world if you sob. She was made to stand outside to cry alone, and they only allow her back in once she repressed her grief. It was brutal, and cruel. That was my first reminder of a culture and tradition I had no awareness of, but was firmly a part of.

The aunts and cousins all stared at me curiously, this familiar stranger in their midst, the chubby-by-asian-standards, foreign relative with the funny accent.

“Is she the servant? Why is her skin so dark? ” I heard one of the younger cousins whisper to her mum. “No, she’s just from Australia. It’s very sunny there,” my aunt replied, referring to my darker than usual Asian skin. “Your grandma raised her before they moved to Australia.” She peered over her glasses at me, her eyeballs examining and judging every inch. I was suddenly very aware of the fact I hadn’t changed my undies in over 30 hours and I just knew she could tell.

“DO. YOU. REMEMBER. ANYTHING?” My aunt spoke to me slowly, loudly and with hand gestures, like she was Jodie Foster from Nell, speaking to a box of hair. I shook my head. Not really, I replied, quietly ashamed of my inability to prove my blood worth to her.

Outside in the corridor, I can hear an argument. “No. She’s in way too much pain to leave.” My oldest aunt hissed.

“Mum would have wanted to die at home. You KNOW how much she hates hospitals.” My mum, the youngest sibling, replied with a confidence and authority I’ve never heard from her. It made my heart sing with a strange sense of pride.

A long silence followed.

“I know you were always her favourite,” my aunt responded coldly, “but where were you the last twenty years. Where were you before she was dying.” That’s the thing I’ve learnt about deaths – it is the key to searing open old family wounds that you thought were long healed.

The doctor came in and made the decision for us. Her blood pressure had dropped so low there was nothing more the hospital can do. They took her off painkillers, and removed all the tubes from her body. Immediately, her body jerked and spasm-ed from the pain. She started whimpering, and out of the corner of my eye, I saw my mum leave the room, before hearing her muffled sobs drifting in from outside. I only saw my mum cry once that entire trip. But I heard her, almost every night when she thought I was asleep. In Taiwanese culture, crying over death is not only a sign of weakness, but also a form of disrespect to the dead. I just wished I was able to carry some of my mum’s anguish and pain of losing her mother.

All the grandchildren were queued up to say goodbye. Someone remembered grandma is deaf in one ear, but no one can agree on which ear. So instead, we were told to shout, “it’s time to go grandma” in her general direction, like some sort of really fucked up big brother eviction. They went around the circle, one by one, shouting. I looked down at my feet the entire time, for fear of breaking down and being made to go stand outside. But when it got to me, they completely skipped past me, on to the next grandchild in the line, and I was never given the opportunity to say my goodbye. I looked around at everyone, stunned and embarrassed, hoping someone would notice, give me my chance. But no one did, and worst of all, I didn’t say anything. I didn’t stop them.

At that point, my grandma went into a massive, final fit. Instinctively, I grabbed her hand, and was surprised to find it was still warm.

And then, I experienced a strange, ethereal memory flood. I drowned in memories.

Clutching her hand as a 6 year old, walking to the local fish market, asking her why I lived with her and not with my parents like all the other kids, to which she replied, in the no-bullshit Taiwanese way, “It’s because they are young, and they don’t love you enough…But they will.”

When I was 9, refusing to let go of her hand at the airport. “But I don’t want to go to Austria!” I demanded, before my parents coaxed me onto the plane with the promise of pancakes that I eventually threw up 9 hours later, somewhere over Brisbane.

I remember when I was 14, the first and only time she ever visited Australia, I refused to hold her hand or even be seen near her, because I was an embarrassed teenager, and it was the height of the Pauline Hanson era, and I was afraid that if my carefully curated group of only white friends saw me with her, they’d finally realise I was Asian.

When I was 20, and went to Taiwan with 2 of my friends, and only made myself available to see her once, because I was a self-involved uni student on summer holidays and just wanted to hang out with my mates. But that time, the last time I saw her alive and healthy, as I mumbled a vague goodbye to her, she pulled out from her pocket a round, green Taiwanese stone fruit, one I had never seen before, placed it in my hand and held it tightly. “Look at you now,” she beamed up at me. “Look how tall you are.” (I’m actually really tall in Asia). “Go live the life you can’t have here. You will, won’t you?”

As I looked down at her fading body through my watery vision, she opened her eyes. The doctors were right – she could hear everyone’s goodbyes this entire time. Everyone’s, except mine. And she was crying. She was so afraid of death and in so much pain. Her top was completely soaked through with bile, leaking from the stitches of her shattered body. “Don’t be afraid,” I wanted to say. But still, no words came out. And then – she was gone. I felt her hand fall from mine, as firecrackers marking day 2 of Chinese New Year went off outside.

She always said she didn’t want to die on New Year’s day.

It dawned on me that even though I’ve spent most of my adult life questioning what it meant to be an Australian, never once did I question what it meant to be Taiwanese. I’ve never needed to, because heritage and family is something that lives in the crux of my soul, even despite my best attempts to escape it. As I stood there, trying to measure the loss of the woman who raised me, I felt a warm hand on my shoulder. “You’re bleeding”, my mum said, pointing at an open superficial scratch on my hand. I hadn’t even noticed.

She ran a cloth under some warm water, and then out of nowhere, she bemused; “Fried chicken. That’s where you get it from you know.” My mum looked me. “Your grandma. She loooved fried chicken.” And for the briefest moment, her walls were down. I wondered if this was going to be our Gilmore Girls moment, where we would gossip and talk about our feelings and menstrual cycles and laugh and cry together. But then, nothing. As I watched my mum wash the blood that has now snaked a trail down my forearm, that moment disappeared as fleetingly as it appeared, lost in the void between blood and water.

Even right now, writing this, I still don’t fully understand why I couldn’t bring myself to say anything to my grandma in that particular moment. I guess I’ve never really known what to say to people in need. Grief, heartbreak, loss. These are emotions I’m ill equipped to deal with. The death of a loved one, of family, is such a profoundly personal experience. And in that moment, I had felt like such an imposter, a pretender, crashing in an intimate family point in time I clearly felt like I didn’t belong in.

Sometimes, when I’m alone at night, I imagine a memory where I got my chance again. Where I looked at my grandma and smiled, I held her hand, and told her that she was right, I did go live the life I couldn’t have had in Taiwan. I followed my creative passion, much to the initial (and ongoing) dismay of my parents. I was lucky enough to find love, a great, significant love, followed by an even greater heartbreak. But in the ashes of that destruction I discovered a better version of myself that I never knew existed. That she can let go in peace, because we’re all going to be okay.

But then I’d realise it’s not a real memory, and I’m still here, with a lifetime’s worth of stories I’ll never be able to share, struggling to move beyond the emptiness and regret that fills my heart, all because of that moment I wish I could take back.

© Corrie Chen, 2015

Photos of the wonderful event can be found here.